Special Operations Executive – Belhaven Hill STS 54B

The Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) had been established in July 1940 with the aim, in Churchill’s words, of “Setting Europe ablaze”. It was responsible for organising sabotage and subversion in Occupied Europe and its agents, men and women, were ultimately to operate in every country held by German Forces. Sometimes alone, sometimes operating with local resistance groups, S.O.E. agents were instrumental in undermining Nazi Germany’s ability to control its ‘empire’.

Maintaining Wireless Communications With Europe

The work of S.O.E. depended upon maintaining good communications with its agents and groups in Occupied Europe. Through such wireless traffic S.O.E. was able to monitor events across the Channel as well as keeping in touch with its agents. In order to help carry out this work Belhaven Hill in Dunbar was requisitioned in June 1943 and soon after a number of female trainee wireless operators, members of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (F.A.N.Y. - the cover organisation to which many female S.O.E. operators belonged) arrived in Belhaven. The officer in charge was Major ‘Pat’ Patterson. The leading F.A.N.Y. officer was Ensign Margaret Daniels.

Wireless Operators at work on Marconi CR100 wireless receivers later in the war.

Training S.O.E. Wireless Operators

Belhaven Hill played a key role in training wireless operators for S.O.E. and was the second such school to open. Its designation was Special Training School No. 54B. In Belhaven Hill trainee W/T operators were taught all the rudiments and skills of Morse telegraphy and were able to practice and hone their Morse Code and key operating skills by sending messages to Special Training School No. 54A at Fawley Court, just north of Henley-on-Thames, some 390 miles away. Actual contacts with agents were not part of Belhaven Hill’s normal duties, though some believe some contact with agents in Scandinavia may have been undertaken.

Belhaven Hill Reminiscences

In 1994 Margaret Turner wrote in relation to the high degree of secrecy permeating their work that, “…[she was] sorry the Dunbar residents thought we were, shall I say reserved, but it had to be.” [Source - personal letter 22.9.1994].

Marion Jones revisited Belhaven Hill in 1999 and is pictured talking to George Angus on Belhaven Hill’s steps.

Margaret Hunter and her twin sister, Jean: F.A.N.Y.s

Marion Jones - F.A.N.Y. & S.O.E. Wireless Operator

Marion became a F.A.N.Y. on the 6th December 1943 and trained at Belhaven Hill between March and May 1944. She was drawn to the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, the F.A.N.Y, after she’d been evacuated as a schoolgirl to Foy in Cornwall. There she stayed with an army major and his wife and a member of the F.A.N.Y.s had come visiting on leave. Marion liked her and her uniform and she thought that if the war lasted long enough, she’d like to join. Two or three years later she’d been told by a friend that the F.A.N.Y.s were recruiting, and she had applied and been accepted. She trained at Banbury in Oxfordshire and at Fawley Court before being sent north to Dunbar. She was training as a wireless operator and for the first time did night duty after she's arrived at Dunbar. There she was able to work on advanced radio sets and felt that the atmosphere was ‘operational’ in tone.

After Dunbar she went back to Fawley Court and was there when the Second Front opened up, before being posted to the fully operational station at Grendon Underwood. While there Marion was in touch with agents in Europe on a daily basis and remembers the highly intensive work undertaken at the time of Arnhem. The wireless operators were only on air for a maximum of nine to ten minutes due to security concerns and Marion remembered the desperate nature of messages at this time. She and her colleagues had been taken off the wireless sets and sent into the teleprinter room and asked to stand over the teleprinter and check the messages. The nature of the messages alerted her to the gravity of what was happening. Messages were being decoded and sent from Grendon Underwood to HQ at Baker Street. She recalled two messages in particular: the first told of “Five crack Panzer divisions advancing” and the other, sent from a distraught agent simply read, “ If you can’t send us the equipment [arms, etc.] you can pack in your bloody war!” She found such messages quite frightening since she’d never read messages in plain English before, previously she had only dealt with coded ones.

While at Belhaven Hill Marion remembered others, who worked there at the same time: The Hunter twins, who also helped with the cooking; Ken Shakeshaft; Sgt Sanderson; Sgt Grey and F.A.N.Y.s like Angel Armstrong, Jilly Lightfoot, Pamela Brain and Norma Lavery. She remembered the Jedburghs (see below) training there but said that they were kept strictly separate, though the girls had a pretty good idea that they were being trained as agents and were likely to be parachuted into France, etc.

Marion found Dunbar a very popular posting, after all it was a much quieter and more peaceful place after Blitz-ravaged London. She found the work interesting and the station ‘homely’. She found the training at STS No. 54b was more advanced than she’d undergone at Fawley Court. The social life was good too. She and her friends often went to the officers’ club for dances, to the Church of Scotland canteen, to restaurants like El Greco and the Lauderdale. The chippy was patronised as was the Railway Inn. The cinema proved popular and was visited a lot. There Marion watched films such as ‘They met in the dark’, ‘Colonel Blimp’, ‘The youngest profession’ and ‘A quiet wedding’. On Sundays there was Church parade which she found enjoyable though quite ‘official’.

An ill-timed dockers strike and the dropping of the atom bomb denied Marion the opportunity to go to the Far East where she was posted in 1945. She left S.O.E. in November 1945.

Margaret Weatherill

Margaret Weatherill was sent to Belhaven Hill for training. In 1999 she wrote:

“…I was only there [Belhaven Hill] for six weeks in 1943… Several of us F.A.N.Y.s were sent there after we had finished our W/T training at Fawley Court, Henley on Thames,* in order to get used to sending messages to the Signal Station at Grendon Underwood [STS 53A] as opposed to working to our instructor at the end of a table. We then went operational at Grendon as fully-fledged Wireless Operators. After a short while I volunteered to go abroad, firstly to Algiers and subsequently to Italy, working with S.O.E. agents behind enemy lines, where I stayed till V.E. Day.”

[Source – Private letter, 1st January 1999] [* - main F.A.N.Y. W/T training station]

Elizabeth Dean (née Medd)

Elizabeth Medd was also sent to Belhaven Hill. She went there to assist with a pre-D-Day exercise. She described her time in Belhaven thus:

“I was sent up to Dunbar from STS 53A to help with the coding and decoding of the messages during the pre-D-Day exercise. I was a F.A.N.Y. and nineteen years old, the only experienced codist there, the others being trainees. I worked the eight to twelve morning and evening shift and did a little extra work helping in the kitchen, etc. It was a pleasant break from the responsibility of an operational station, where one lived and slept codes for twenty-four hours a day.

One day I managed to break an indecipherable that had come in. It was not very difficult. As I remember, the code was the usual double transposition and the coder had managed to twist some of his columns, ‘hatting’ I think it was called, resulting in slipped letters; a type of indecipherable I used to think of as my speciality and enjoy solving. Later, in Broadway, I met a Captain who remembered me as the clever girl who broke the indecipherable. I was very flattered!

As it was February I had been kitted out before leaving Grendon with all sorts of woolly comforts that had come from Canada. In fact, the weather was not very cold. Although the west winds were very blustery at times, there was plenty of sunshine and I had some lovely afternoon walks up into the hills and along the beach. The local people seemed very friendly and hospitable and I remember wondering why the Scots were thought to be dour.

I managed to get one weekend off during the few weeks I spent in Dunbar. I went to Edinburgh by bus and stayed a couple of nights with the mother of a F.A.N.Y. friend at Grendon, a Mrs Watson Wemyss, who lived in one of the lovely, tall Georgian terrace houses which abound in the city. She generously showed me the sights, including the stone called the Heart of Midlothian, on which she said it was the custom to spit. I did so immediately, rather to her surprise. I particularly remember the wonderful snowdrops in the woods beyond the [Forth] and, of course, the castle and the palace of Holyrood.”

[Source – Personal letter, 1 January 1999]

Relaxation

The work at Belhaven Hill was demanding and tiring. It required long periods of 100% concentration. To relax, the F.A.N.Y. W/T trainees could play squash, exercise in the hills and on the coast and visit Edinburgh. The Turner twins, like Ken Shakeshaft, made good use of the building’s squash court for relaxation. They could also, as Marion Jones described, visit attractions closer to home, in Dunbar. Anne Martin, a F.A.N.Y. there from September/October 1943 till January 1944, remembers how she and her colleagues “…congregated off-duty at the Lauderdale Café in Dunbar where the Togneri family always [made] us feel welcome. They were very kind to us.”

Jedburghs

In 1942 forward planning for the Overlord landings had raised the question of how the French Resistance forces could best be employed in support. Three-man units code-named ‘Jedburghs’ were envisaged by S.O.E.’s Lt Col. Peter Wilkinson as a means of raising the effectiveness of the varied and often poorly organised Resistance units operating throughout France before the D-Day Landings. The code name ‘Jedburgh’ had nothing to do with the Scottish Border town, it was simply the code name chosen for this operation.

From the 3rd to the 11th March 1943, an exercise involving eleven Jedburgh units and codenamed ‘Spartan,’ was held on Salisbury Plain to test the idea. STS 54B at Dunbar acted as the receiving centre for the messages broadcast by the wireless operators, who formed a third of each Jedburgh team. The exercise was very successful, and the concept was soon translated into reality. Recruits were sought, both in the UK and in America, and the chosen exposed to the rigours of a severe training programme in Britain. Many didn’t complete the course.

Training Jedburghs At Belhaven Hill

By combining the talents and language skills of a mix of American, British, French, Dutch and Belgian officers and men, it was hoped to maximise the chances of effective use of and communications with the Resistance units. In addition to the two officers each Jedburgh unit contained a wireless operator (often a non-commissioned officer) and Belhaven Hill trained all of these men, a total of some 100. The Jeds, as they often called themselves, were kept strictly separate from other operators for security reasons.

That they were something a little different couldn’t help but be noticed by the other trainees, not least because many of the Jedburgh wireless operators trained at STS 54B were American. Many British Jedburgh wireless operators came from tank regiments where, in addition to their existing wireless experience, they had already received instruction in a wide range of pertinent skills, e.g. field craft and map reading. Their training lasted between one and two weeks at Belhaven Hill.

The first Jedburgh units went into action in France on the 5th June 1944, the forerunners of a total of ninety-three. All Jedburgh agents were sent in in uniform, a real but often slight protection against execution as spies. Even with this minimal protection twenty-one of these men were to lose their lives.

Arthur Brown Remembers

Arthur Brown, a former Jedburgh W/T operator, spent some time at Belhaven Hill. He wrote:

“The training at Dunbar from March 1944 onwards was, I believe, largely a confidence building exercise to enable W/T operators to test the kinds of radio equipment they would be using in the field, and over the same distances. The rotation of the 100 or so Jed operators through Dunbar was done in groups for about a week or ten days per group. I went with the first group all of whom were destined to parachute into Southern France from Algiers, although [we] did not know it at the time.”

[Source - Personal letter - 13 Oct. 1998]

Arthur Brown: Jedburgh Agent.

Ron Brierley Remembers

Ron Brierley was also sent to Belhaven Hill and here he describes his experiences after joining SOE in 1943, becoming a Jedburgh and training as a W/T operator:

“Small groups of us occasionally went to Belhaven when we were stationed in Scotland on exercises – we worked our radio scheds back to either Belhaven or Henley, simulating the distances we should have to cover from France. I went there on two occasions but only for a few days at a time and memory is pretty vague.

I do know I was there at New Year 43/44 with a small group – we went into Dunbar in the evening and had a high old time – afraid we were a bit ‘over the top’ and got into bother with the police – one of my pals ‘Cobber’ Cain was locked up for the night –something to do with a policeman’s helmet – which they didn’t appreciate. There was quite a fuss – the telephone lines were buzzing, and we were all quite glad to get back to Milton.”

[Source – Personal letter 11th October 1998]

Ron later went to France on two operations in 1944 to Brittany and then Doubs. Finally, he was sent out to Burma for a Jedburgh operation in the Sittang Valley (Operation Reindeer) and then to Sumatra and home.

Eric John (Jack) Grinham Remembers

Jack came to Belhaven Hill with a small group of Jedburghs, seven in all, to undergo training. In 1998 Jack wrote:

“We used to operate at night and used an open-ended shed, though I can remember clearly that in the rafters was a Swallow’s nest… the bird was sitting quite undisturbed by us. I used to walk into Dunbar with others... to patronise the ‘Church of Jocks’ as we called the Church of Scotland Forces canteen.”

[Source – Personal letter: 3rd November 1998]

An Instructor Remembers: Ken Shakeshaft

Ken spent some time at Belhaven Hill instructing the F.A.N.Y.s in Morse Code. His story (which is an amalgamation of two letters) gives a very good picture of life at Belhaven Hill:

“From Fawley Court I went to Belhaven in the summer or autumn of 1943. At that time the place was a ‘bit of a lash up’ and my function was simply to teach F.A.N.Y.s the Morse Code and Q Code and how to tune a receiver. In between times I was helping John Tierney to get his transmitter hut working. No easy task erecting a forty-foot steel mast in a gale that seemed never to end on that headland. The constant high wind meant that some of the F.A.N.Y.s became hysterical and had to be sent south.

Then came the instruction to arrange dummy traffic, call signs, frequencies, days and times and writing messages in blocks of five letters. They were meaningless, of course. Fortunately, we had a few trained operators. How long these transmissions went on for I cannot remember. To me at the time it was a bluff, but because of SOE security I was not told anything. S.O.E. was almost excessively security minded so that I didn’t know the purpose of the station, but from hearsay I understand it was working to Denmark in the person of Mr Bang of Bang and Olufsen.

Back to my arrival at Belhaven: the staff consisted of Lieutenant Pat Paterson, John Tierney, two other bods like myself and that was all. Then there were the F.A.N.Y.s. We used to sit around in small groups in empty rooms trying to teach Morse. I say trying, but obviously most of the girls became good enough to operate. The Germans listening in must have had an interesting time.

I remember that for me it was the most comfortable billet of my six years in Signals. I had my own bedroom, furnished and with sheets on my bed and I was only a Sergeant at the time. I certainly fed well [and was introduced] to drinking tea without milk.

…a picture of the signal office at Belhaven [shows] each operator has an automatic key activated by a punched paper tape; the short loop of tape visible would be a call sign. A great advance from my day …”

[Source – Personal letters, 5th October 1998 & 18th January 1999]

Ken included some interesting conjecture, which gives us a good example of both the guesswork security imposed on people like the members of staff at Belhaven Hill and of the enticements of hindsight. He wrote that the following were “…assumptions because [he] was not personally involved”:

“Belhaven wireless station was involved with communications leading to the finding of the Bismarck and the attack on the Tirpitz and the sabotage of the heavy water plant in Norway. Sometime after the latter event I had a surprise visit from a Lieutenant in the Norwegian navy who had taken part in the operation, who came to Belhaven to thank the station for our excellent training of the W/T operators”.

A Dedicated Jedburgh

During the night of 7/8 June 1944, just after D-Day, Jedburgh Team Isaac, which had flown from RAF Fairford, was blind dropped by parachute near Nièvre in what is now Morvan Region National Park. Their area of operations included Aubingy sur Nère, Haddington’s twin town. One member was Captain Idris Isaac, a member of the Parachute Regiment of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. Born in 1915, Idris was a trained chemist and was probably included in order to manufacture or maintain explosives for use by the Maquis in sabotage. He travelled under a false passport in the name of Paul Emile Bois, despite knowing little French and being a red headed Celt! Sergeant J. Sharpe, the team’s wireless operator, could easily have trained at Belhaven Hill. Team Issac co-operated with Team Harry in aiding local Maquis units to disrupt communications used by German units being sent north to Normandy.

The leader of the team was Lieutenant-Colonel JRH Hutchison, a former World War One soldier who led RF section of SOE and had been set the awkward task of getting de Gaulle’s FFI officers back into France. Co-operation between the British, Americans and the French was difficult at all levels, partly thanks to British and American distrust and partly thanks to inter-French political differences. Added to this mix was the peppery nature of General De Gaulle, recognised as the head of French Resistance groups but resident in England and hemmed in by less than fully trusting allies. Nonetheless, when the Jedburgh operation was set in motion Hutchinson was so keen to get back into operations that he underwent plastic surgery, changed his name and joined Team Isaac! He was also initially responsible for a concurrent political mission, codenamed Verveine. Certainly, his capture would have been a very useful coup for the Germans! The third member was a French officer, Lieutenant Colonel FG Viat who did not arrive at the same time as the first two did.

Today a wall plaque in Haddington’s twin town of Aubingy sur Nère exists which honours the Jedburgh agents of S.O.E. In addition, the war memorial in Aubingy mounts an additional plaque, one dedicated to Belgian Special Parachute Forces and prominently sited below the boots of the ubiquitous Poilu. Perhaps Team Isaac can claim part of the honour.

Noe Czupper (Alan Grant) in Rome

[Courtesy of George Robertson]

Two Jedburghs - Eric Schwarz (Eric Sanders) and Noe Czupper (Alan Grant)

George Robertson very kindly got in touch recently and supplied the following account of his family's relationship with two Belhaven SOE trainees, Eric Sanders and Alan Grant. This is his story:

"Eric Sanders and Alan Grant at Belhaven Hill STS 54b

In 1944, my family lived in Belhaven Village, just over the wall from Belhaven Hill School which had been requisitioned for wartime use. Although we did not know it at the time, Belhaven Hill had become SOE Special Training School STS 54b and was being used for training wireless operators of the SOE, either for listening posts in the UK or for deployment into occupied Europe. Women operatives were given the rank and uniform of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY). The men retained the rank and uniform of their previous unit.

Dunbar was full of young service personnel at the time. The town was also home to 165 Officer Cadet Training Unit with about 200 cadets under training at any one time. Although STS 54b was a secret unit, the personnel were able to hide in plain sight amongst so many other young service personnel in the town.

Although I was just a toddler at the time, my two sisters were in their late teens, and they met two young men at a local social function who they introduced as Eric Sanders and Alan Grant. They became family friends and frequent visitors to our house. This was not uncommon in wartime Dunbar. With so many young people in the town, maybe away from home for the first time, many were “adopted” by local families during their stay.

Eric turned out to be a talented pianist who could play anything from Beethoven to jazz, and he was much in demand at local youth club functions. When their time was up in Dunbar they moved on, promising to keep in touch. We, of course, had no idea what their final destination would be. They both survived the war, and it was many years later when we discovered the true story of their wartime service.

We discovered that Eric Sanders and Alan Grant were not their real names. SOE policy was to give agents deployed into Europe anglicised names in case of capture and they were given some freedom of choice as to what names to use. Eric was originally Erich Schwarz, whose Jewish family escaped from Austria soon after the Anschluss. They were fortunate in having relatives in London who could sponsor them. Alan Grant was originally Noe Czupper and was from Hungary.

Both were transferred to SOE HQ in Bari, Italy, to await deployment. Alan Grant was parachuted into Yugoslavia to support Tito’s partisans. He survived the war and subsequently emigrated to South America.

Eric Sanders was due to deploy to Southern Austria, but the resistance group he was to support was compromised and all were arrested and executed. Eric’s deployment was cancelled. Eric worked in Vienna post-war for two years before returning to UK. There he worked as a teacher in London Inner City comprehensives and stayed in touch with our family in Dunbar. He retained his new name of Eric Sanders for the rest of his life.

Eric lived to the age of 101. He was a very talented man and a prolific author. His autobiography mentions his time in Dunbar and he has written a number of historical novels based around wartime Vienna. He given the “Decoration of Honour” by the President of Austria (that country’s highest civilian award) for his work both during and after the war in support of Austria.

You will find his obituary here:

https://www.jewishnews.co.uk/eric-sanders-death/"

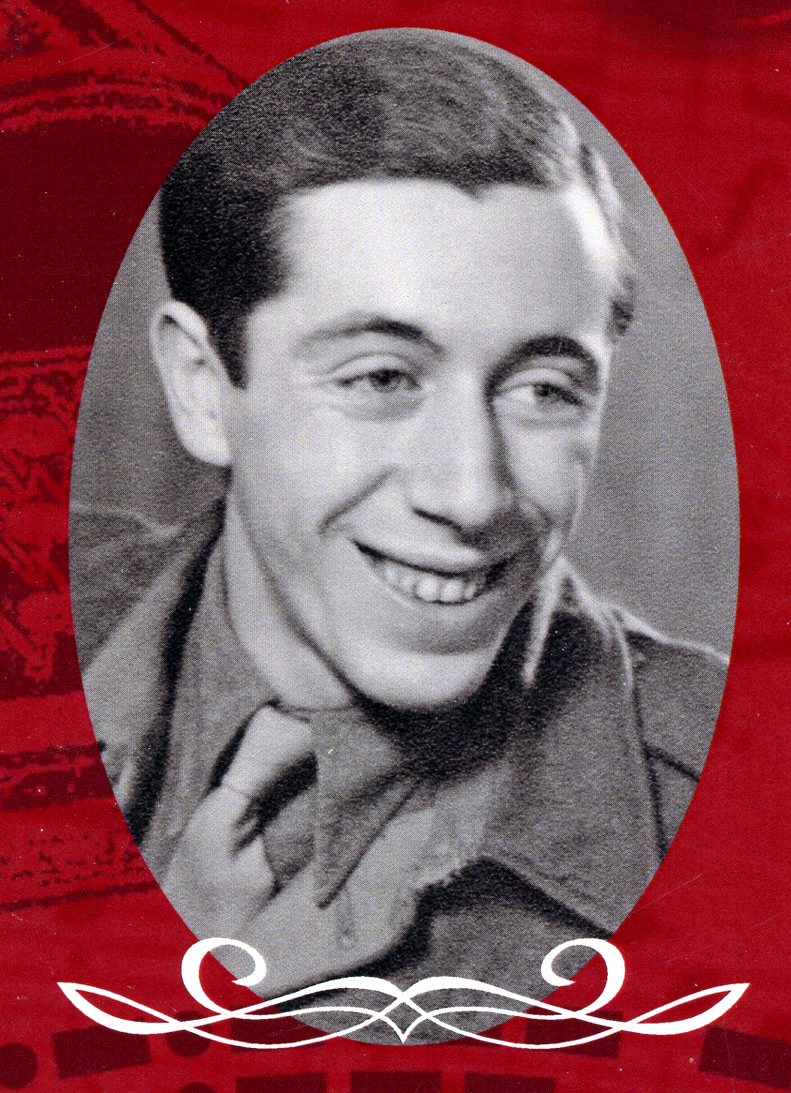

Eric Schwarz (Eric Sanders) on the cover of his autobiography, "Secret operations: from music to morse and beyond."

[Courtesy of George Robertson]

Special Force Signal Units

The range of S.O.E. groups to use the facilities of Belhaven Hill included others beyond Jedburghs. David Finlay-Maxwell was involved and here he describes his experiences as a communications link between S.O.E HQ and field agents. He wrote:

“First let me explain that we primarily used 54B as a base rather than as a training location: we used to arrive as a complete unit, with our instructors. We were, however, always given every cooperation and support. The F.A.N.Y.s handled code work and Morse, both in and out. We had three, Special Force’ units, SF1, 2 and 3. Our task, once the landings were completed, was to maintain communications between the UK, the Army Group’s SOE Intelligence Corps and field agents. These units were completely self-contained and mobile, carrying our own transmitters, receivers, generators, etc., on (very) large GMC trucks and trailers…The correct radio frequencies to use at any time depended (largely) on the distance/separation between the ‘remote’ transmitter and your receiver. To simulate what we expected to find in the ‘field’ we decided to use Doncaster as the first stage and Dunbar as the second: this worked out fairly well and revealed many potential mini-disasters.”

[Source – Personal letter, 5 March 1999]

Conclusion

Belhaven Hill STS 54B can be seen to have fulfilled a very important training role in the secret activities of Special Operations Europe and to have provided the wireless training for any number of agents and W/T operators.